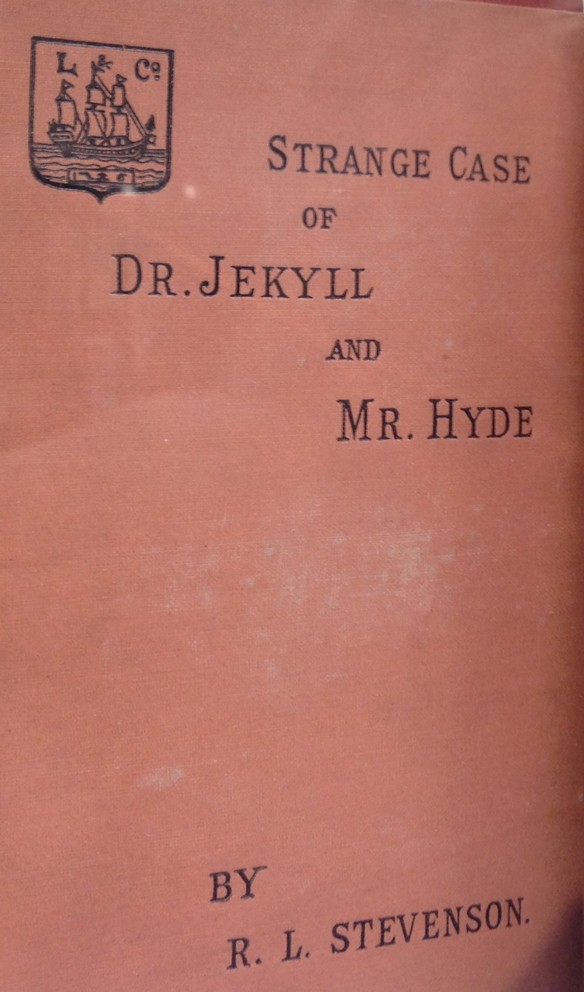

There are few authors who add phrases to our everyday language, but the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson managed it. In 1885, in the soft southern town of Bournemouth — whence he had repaired so that his ill health could benefit from the fresh sea air and warmer climate — he wrote Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

(The definite article is missing from the original title. No-one is sure why, but it adds to the strangeness.)

Stevenson may have given us the phrase Jekyll and Hyde, but we furiously mispronounce it. He intended for the first name to be enunciated as all good English families enunciated it: GeeKill, with a long E. (Perhaps we’re just contrary.)

The manuscript has its own history of good and evil. The author’s wife burned the first draft, it is well known. Or Stevenson himself did… Or someone did, didn’t they?

The splendidly named Frances Matilda Van de Grift — known as Fanny — was Stevenson’s American spouse. She had earlier been married to Samuel Osbourne, a union which had produced the children Isobel and Lloyd. She and Stevenson met in Grez, a retreat in Fontainebleau. Fanny was studying art and Robert was completing a French canoe voyage with Sir Walter Simpson (as you do). Robert and Fanny married in California in 1880.

“Strange Case” came about because publisher Charles Longman asked Stevenson for a ghost story for the Christmas edition of his magazine. Lloyd Osbourne, Stevenson’s stepson, remembered the writing of the tale well: “Louis came downstairs in a fever; read nearly half the book aloud; and then, while we were still gasping, he was away again, and busy writing. I doubt if the first draft took so long as three days.” 1

However long that first draft took, it didn’t matter. It was, so all the stories tell us, burned. When Fanny, Lloyd’s mother, read it, she told Stevenson that it was “utter nonsense” and he had “missed the allegory”. On contemplating this criticism, Stevenson cast the draft onto the fire. “Imagine my feelings,” wrote Lloyd, “as we saw those precious pages wrinkling and blackening and turning into flames.”

If we are to believe Lloyd, the next draft also took another mere “three days of feverish industry”. Stevenson’s letters show that the writing actually took around six weeks. A full draft of the work is still in existence (at the Pierpoint Morgan Library in New York, while there are 24 pages at Yale and some at Princeton).

Did any burning at all go on? Yes, but none of it by Fanny Stevenson.

Her criticism, however, is fascinating. In what way had Stevenson’s first draft “missed the allegory”? What is the book an allegory of? By day, the good Dr Jekyll goes about his work as a scientist; by night, the evil Mr Hyde wreaks violence on the streets of London. Are we all monsters beneath our thin coating of civilisation? Do we all have it in us to kill? It’s because the book makes us consider these questions that it is still read today, many years after we have learned the original “twist”, that Jekyll and Hyde are the same being.

We will never know what the first draft contained, as it is in ashes, all agree, even if not all agree as to the who and the why. However, the story as published is certainly toned down from what we can read in the surviving second draft. In the draft, we learn that Jekyll became “in secret the slave of certain appetites“. 2 (The appetites are not enumerated.) In the published book, the doctor is guilty merely of “a certain impatient gaiety of disposition”.

Was the first draft full of appetites spelled out in detail? Is that what so shocked Fanny, rather than a (usually less chilling) lack of allegory? Did a rational desire to protect his reputation as a children’s author (A Child’s Garden of Verses) cause Stevenson to hurl a series of sordid sexual shenanigans into the flames?

We can speculate all we like. We’ll never know. But that’s the fun.

1 Balfour, Graham (1912). The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson II. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 15–6.

2 Dr Jekyll MS at the British Library

The cover of the first edition of Strange Case. The definite article is definitely missing. Strange.